Great Slave Lake

| Great Slave Lake | |

|---|---|

|

|

| False-color photo of Great Slave Lake | |

|

|

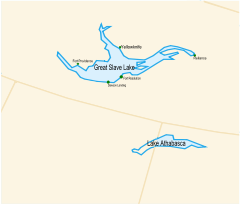

| Map of Great Slave Lake and Lake Athabasca | |

| Location | Northwest Territories |

| Lake type | remnant of a vast glacial lake |

| Primary inflows | Hay River, Slave River |

| Primary outflows | Mackenzie River |

| Catchment area | 971,000 km2 (374,905 sq mi)[1] |

| Basin countries | Canada |

| Max. length | 480 km (300 mi) |

| Max. width | 109 km (68 mi) |

| Surface area | 27,200 km2 (10,502 sq mi)[1] |

| Average depth | 41 m (135 ft)[1] |

| Max. depth | 614 m (2,014 ft)[1] |

| Water volume | 1,580 km3 (380 cu mi) |

| Shore length1 | 3,057 km (1,900 mi)[1] |

| Surface elevation | 156 m (512 ft)[1] |

| 1 Shore length is not a well-defined measure. | |

Great Slave Lake (French: Grand lac des Esclaves) is the second-largest lake in the Northwest Territories of Canada (behind Great Bear Lake), the deepest lake in North America at 614 m (2,014 ft),[1] and the ninth-largest lake in the world. It is 480 km (300 mi) long and 19 to 109 km (12 to 68 mi) wide. It covers an area of 27,200 km2 (10,502 sq mi)[1] in the southern part of the territory. Its volume is 2,090 km3 (500 cu mi). The lake shares its name with the Slavey North American Indians. Towns around the lake include: Yellowknife, Fort Providence, Hay River and Fort Resolution. The only community in the East Arm is Lutselk'e, a hamlet of about 350 people, largely Chipewyan aboriginals of the Dene Nation.

Contents |

History

First Nations peoples were the first settlers around the lake, building communities including Dettah, which still exists today.

British fur trader Samuel Hearne explored the area in 1771 and crossed the frozen lake, which he initially named Lake Athapuscow (after an erroneous French speaker's pronunciation of Athabaska).

In 1897-1898, the American frontiersman Charles "Buffalo" Jones traveled to the Arctic Circle, where his party wintered in a cabin that they had constructed near the Great Slave Lake. He captured five baby musk oxen, which were thereafter slaughtered by superstitious Indians.[2]Jones's exploits of how he and his party shot and fended off a hungry wolf pack near Great Slave Lake was verified in 1907 by Ernest Thompson Seton and Edward A. Preble when they discovered the remains of the animals near the long abandoned cabin.[3]

In the 1930s, gold was discovered there, which led to the establishment of Yellowknife, which would become the capital of the NWT.

In 1967, an all-season highway was built around the lake, originally an extension of the Mackenzie Highway but now known as Yellowknife Highway or Highway 3.

On January 24, 1978, a Soviet Radar Ocean Reconnaissance Satellite, named Cosmos 954, built with an on board nuclear reactor fell from orbit and disintegrated. Pieces of the nuclear core fell in the vicinity of Great Slave Lake. The nuclear debris was picked up by a group called Operation Morning Light formed with both American and Canadian members.[4]

Geography and natural history

The Hay, Slave and Taltson Rivers are its chief tributaries. It is drained by the Mackenzie River. Though the western shore is forested, the east shore and northern arm are tundra-like. The southern and eastern shores reach the edge of the Canadian Shield. Along with other lakes such as the Great Bear and Athabasca, it is a remnant of a vast post-glacial lake.

The East Arm of Great Slave Lake is filled with islands, and the area is within Thaydene Nene National Park. The Pethei Peninsula separates the East Arm into McLeod Bay in the north and Christie Bay in the south. The lake is at least partially frozen during an average of eight months of the year. During winter, the ice is thick enough for semi-trailer trucks to pass over using ice roads. Until 1967, when an all-season highway was built around the lake, goods were shipped across the ice to Yellowknife, located on the north shore. Goods and fuel are still shipped across frozen lakes up the winter road to the diamond mines located near the headwaters of the Coppermine River, Northwest Territories. A ferry is required to access Yellowknife during spring when the ice is not present in a solid sheet along Highway 3 where it crosses the Mackenzie River.

The main western portion of the lake forms a moderately deep bowl with a surface area of 18,500 km2 (7,100 sq mi) and a volume of 596 km3 (143 cu mi). This main portion has a maximum depth of 187.7 m (616 ft) and a mean depth of 32.2 m (106 ft).[5] To the east, McLeod Bay (62 52N, 110 10W) and Christie Bay (62 32N, 111W) are much deeper, with a maximum recorded depth in Christie Bay of 614 m (2,014 ft).[1]

On some of the plains surrounding Great Slave Lake, climax polygonal bogs have formed, the early successional stage to which often consists of pioneer Black Spruce.[6]

South of Great Slave Lake, in a remote corner of Wood Buffalo National Park, is the nesting site of a remnant flock of Whooping Cranes, discovered in 1954.[7]

Ice road

There is one ice road on Great Slave Lake, the Dettah ice road, which connects from Yellowknife, the capital of the Northwest Territories to Dettah, also in the Northwest Territories.

See also

- List of lakes by depth (8)

- List of lakes by volume (12)

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 1.6 1.7 1.8 Hebert, Paul (2007). "Great Slave Lake, Northwest Territories". Encyclopedia of Earth. Washington, DC: Environmental Information Coalition, National Council for Science and the Environment. http://www.eoearth.org/article/Great_Slave_Lake,_Northwest_Territories. Retrieved 2007-12-07

- ↑ "C.J. "Buffalo" Jones". skyways.lib.ks.us. http://skyways.lib.ks.us/history/cjjones.html. Retrieved September 3, 2010.

- ↑ "Buffalo Jones". h-net.msu.edu. http://h-net.msu.edu/cgi-bin/logbrowse.pl?trx=vx&list=h-shgape&month=0008&week=c&msg=4ZaC2nPza053qdx7jtInAg&user=&pw=. Retrieved September 4, 2010.

- ↑ Natural Resources Canada. "Operation Morning Light". http://gsc.nrcan.gc.ca/gamma/ml_e.php. Retrieved 2007-01-24.

- ↑ Schertzer, W. M. (2000). Digital bathymetry of Great Slave Lake. NWRI Contribution No. 00-257, 66 pp.

- ↑ C. Michael Hogan. 2008. Black Spruce: Picea mariana, GlobalTwitcher.com, ed. Nicklas Stromberg

- ↑ University of Nebraska. "Whooper Recount". http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/biosciornithology/19/. Retrieved 2007-01-20.

Further reading

- Canada. (1981). Sailing directions, Great Slave Lake and Mackenzie River. Ottawa: Dept. of Fisheries and Oceans. ISBN 0660110229

- Gibson, J. J., Prowse, T. D., & Peters, D. L. (2006). Partitioning impacts of climate and regulation on water level variability in Great Slave Lake. Journal of Hydrology. 329 (1), 196.

- Hicks, F., Chen, X., & Andres, D. (1995). Effects of ice on the hydraulics of Mackenzie River at the outlet of Great Slave Lake, N.W.T.: A case study. Canadian Journal of Civil Engineering. Revue Canadienne De G̐ưenie Civil. 22 (1), 43.

- Kasten, H. (2004). The captain's course secrets of Great Slave Lake. Edmonton: H. Kasten. ISBN 097366410X

- Jenness, R. (1963). Great Slave Lake fishing industry. Ottawa: Northern Co-ordination and Research Centre. Dept. of Northern Affairs and National Resources.

- Keleher, J. J. (1972). Supplementary information regarding exploitation of Great Slave Lake salmonid community. Winnipeg: Fisheries Research Board, Freshwater Institute.

- Mason, J. A. (1946). Notes on the Indians of the Great Slave Lake area. New Haven: Published for the Department of Anthropology, Yale University, by the Yale University Press.

- Sirois, J., Fournier, M. A., & Kay, M. F. (1995). The colonial waterbirds of Great Slave Lake, Northwest Territories an annotated atlas. Ottawa, Ont: Canadian Wildlife Service. ISBN 0662238842

|

|||||||||||